Thinking about the universe

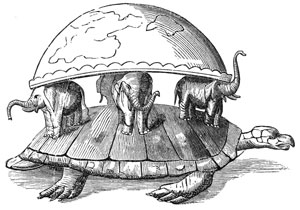

We live in a strange and wonderful universe. Its age, size, violence, and beauty require extraordinary imagination to appreciate. The place we humans hold within this vast cosmos can seem pretty insignificant. And so we try to make sense of it all and to see how we fit in. Some decades ago, a well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the centre of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: “What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant turtle.” The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, “What is the turtle standing on?” “You’re very clever, young man, very clever,” said the old lady. “But it’s turtles all the way down!”

Most people nowadays would find the picture of our universe as an infinite tower of turtles rather ridiculous. But why should we think we know better? Forget for a minute what you know—or think you know—about space. Then gaze upward at the night sky. What would you make of all those points of light? Are they tiny fires? It can be hard to imagine what they really are, for what they really are is far beyond our ordinary experience. If you are a regular stargazer, you have probably seen an elusive light hovering near the horizon at twilight. It is a planet, Mercury, but it is nothing like our own planet. A day on Mercury lasts for two-thirds of the planet’s year. Its surface reaches temperatures of over 400 degrees Celsius when the sun is out, then falls to almost —200 degrees Celsius in the dead of night. Yet as different as Mercury is from our own planet, it is not nearly as hard to imagine as a typical star, which is a huge furnace that burns billions of pounds of matter each second and reaches temperatures of tens of millions of degrees at its core.

Another thing that is hard to imagine is how far away the planets and stars really are. The ancient Chinese built stone towers so they could have a closer look at the stars. It’s natural to think the stars and planets are much closer than they really are—after all, in everyday life we have no experience of the huge distances of space. Those distances are so large that it doesn’t even make sense to measure them in feet or miles, the way we measure most lengths. Instead we use the light-year, which is the distance light travels in a year. In one second, a beam of light will travel 186,000 miles, so a lightyear is a very long distance. The nearest star, other than our sun, is called Proxima Centauri (also known as Alpha Centauri C), which is about four light-years away. That is so far that even with the fastest spaceship on the drawing boards today, a trip to it would take about ten thousand years.

Ancient people tried hard to understand the universe, but they hadn’t yet developed our mathematics and science. Today we have powerful tools: mental tools such as mathematics and the scientific method, and technological tools like computers and telescopes. With the help of these tools, scientists have pieced together a lot of knowledge about space. But what do we really know about the universe, and how do we know it? Where did the universe come from? Where is it going? Did the universe have a beginning, and if so, what happened before then? What is the nature of time? Will it ever come to an end? Can we go backward in time? Recent breakthroughs in physics, made possible in part by new technology, suggest answers to some of these long-standing questions. Someday these answers may seem as obvious to us as the earth orbiting the sun—or perhaps as ridiculous as a tower of turtles. Only time (whatever that may be) will tell.

Contents

-

Chapter 1

Thinking about the universe

-

Chapter 2

Our evolving picture of the universe

-

Chapter 3

The nature of a scientific theory

-

Chapter 4

Newton's Universe

-

Chapter 5

Relativity

-

Chapter 6

Curved Space

-

Chapter 7

The expanding Universe

-

Chapter 8

The big bang, black holes, and the evolution of the universe

-

Chapter 9

Quantum Gravity

-

Chapter 10

Wormholes and time travel

-

Chapter 11

The forces of nature and the unification of physics

-

Chapter 12

Conclusion