Quantum Gravity

The success of scientific theories, particularly Newton’s theory of gravity, led the Marquis de Laplace at the beginning of the nineteenth century to argue that the universe was completely deterministic. Laplace believed that there should be a set of scientific laws that would allow us—at least in principle—to predict everything that would happen in the universe. The only input these laws would need is the complete state of the universe at any one time. This is called an initial condition or a boundary condition. (A boundary can mean a boundary in space or time; a boundary condition in space is the state of the universe at its outer boundary—if it has one.) Based on a complete set of laws and the appropriate initial or boundary condition, Laplace believed, we should be able to calculate the complete state of the universe at any time.

The requirement of initial conditions is probably intuitively obvious: different states of being at present will obviously lead to different future states. The need for boundary conditions in space is a little more subtle, but the principle is the same. The equations on which physical theories are based can generally have very different solutions, and you must rely on the initial or boundary conditions to decide which solutions apply. It’s a little like saying that your bank account has large amounts going in and out of it. Whether you end up bankrupt or rich depends not only on the sums paid in and out but also on the boundary or initial condition of how much was in the account to start with.

If Laplace were right, then, given the state of the universe at the present, these laws would tell us the state of the universe in both the future and the past. For example, given the positions and speeds of the sun and the planets, we can use Newton’s laws to calculate the state of the solar system at any later or earlier time. Determinism seems fairly obvious in the case of the planets—after all, astronomers are very accurate in their predictions of events such as eclipses. But Laplace went further to assume that there were similar laws governing everything else, including human behavior.

Is it really possible for scientists to calculate what all our actions will be in the future? A glass of water contains more than 10 24 molecules (a 1 followed by twenty-four zeros). In practice we can never hope to know the state of each of these molecules, much less the complete state of the universe or even of our bodies. Yet to say that the universe is deterministic means that even if we don’t have the brainpower to do the calculation, our futures are nevertheless predetermined.

This doctrine of scientific determinism was strongly resisted by many people, who felt that it infringed God’s freedom to make the world run as He saw fit. But it remained the standard assumption of science until the earl) years of the twentieth century. One of the first indications that this belief would have to be abandoned came when the British scientists Lord Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans calculated the amount of blackbody radiation that a hot object such as a star must radiate. (As noted in Chapter 7, any material body, when heated, will give off blackbody radiation.)

According to the laws we believed at the time, a hot body ought to give off electromagnetic waves equally at all frequencies. If this were true, then it would radiate an equal amount of energy in every color of the spectrum of visible light, and for all frequencies of microwaves, radio waves, X-rays, and so on. Recall that the frequency of a wave is the number of times per second that the wave oscillates up and down, that is, the number of waves per second. Mathematically, for a hot body to give off waves equally at all frequencies means that a hot body should radiate the same amount of energy in waves with frequencies between zero and one million waves per second as it does in waves with frequencies between one million and two million waves per second, two million and three million waves per second, and so forth, going on forever. Let’s say that one unit of energy is radiated in waves with frequencies between zero and one million waves per second, and in waves with frequencies between one million and two million waves per second, and so on. The total amount of energy radiated in all frequencies would then be the sum 1 plus 1 plus 1 plus ... going on forever. Since the number of waves per second in a wave is unlimited, the sum of energies is an unending sum. According to this reasoning, the total energy radiated should be infinite.

In order to avoid this obviously ridiculous result, the German scientist Max Planck suggested in 1900 that light, X-rays, and other electromagnetic waves could be given off only in certain discrete packets, which he called quanta. Today, as mentioned in Chapter 8, we call a quantum of light a photon. The higher the frequency of light, the greater its energy content. Therefore, though photons of any given color or frequency are all identical, Planck’s theory states that photons of different frequencies are different in that they carry different amounts of energy. This means that in quantum theory the faintest light of any given color—the light carried by a single photon—has an energy content that depends upon its color. For example, since violet light has twice the frequency of red light, one quantum of violet light has twice the energy content of one quantum of red light. Thus the smallest possible bit of violet light energy is twice as large as the smallest possible bit of red light energy.

How does this solve the blackbody problem? The smallest amount of electromagnetic energy a blackbody can emit in any given frequency is that carried by one photon of that frequency. The energy of a photon is greater at higher frequencies. Thus the smallest amount of energy a blackbody can emit is higher at higher frequencies. At high enough frequencies, the amount of energy in even a single quantum will be more than a body has available, in which case no light will be emitted, ending the previously unending sum. Thus in Planck’s theory, the radiation at high frequencies would be reduced, so the rate at which the body lost energy would be finite, solving the blackbody problem.

The quantum hypothesis explained the observed rate of emission of radiation from hot bodies very well, but its implications for determinism were not realized until 1926, when another German scientist, Werner Heisenberg, formulated his famous uncertainty principle.

The uncertainty principle tells us that, contrary to Laplace’s belief, nature does impose limits on our ability to predict the future using scientific law. This is because, in order to predict the future position and velocity of a particle, one has to be able to measure its initial state—that is, its present position and its velocity—accurately. The obvious way to do this is to shine light on the particle. Some of the waves of light will be scattered by the particle. These can be detected by the observer and will indicate the particle’s position. However, light of a given wavelength has only limited sensitivity: you will not be able to determine the position of the particle more accurately than the distance between the wave crests of the light. Thus, in order to measure the position of the particle precisely, it is necessary to use light of a short wavelength, that is, of a high frequency. By Planck’s quantum hypothesis, though, you cannot use an arbitrarily small amount of light: you have to use at least one quantum, whose energy is higher at higher frequencies. Thus, the more accurately you wish to measure the position of a particle, the more energetic the quantum of light you must shoot at it.

According to quantum theory, even one quantum of light will disturb the particle: it will change its velocity in a way that cannot be predicted. And the more energetic the quantum of light you use, the greater the likely disturbance. That means that for more precise measurements of position, when you will have to employ a more energetic quantum, the velocity of the particle will be disturbed by a larger amount. So the more accurately you try to measure the position of the particle, the less accurately you can measure its speed, and vice versa. Heisenberg showed that the uncertainty in the position of the particle times the uncertainty in its velocity times the mass of the particle can never be smaller than a certain fixed quantity. That means, for instance, if you halve the uncertainty in position, you must double the uncertainty in velocity, and vice versa. Nature forever constrains us to making this trade-off.

How bad is this trade-off? That depends on the numerical value of the "certain fixed quantity" we mentioned above. That quantity is known as Planck’s constant, and it is a very tiny number. Because Planck’s constant is so tiny, the effects of the trade-off, and of quantum theory in general, are, like the effects of relativity, not directly noticeable in our everyday lives. (Though quantum theory does affect our lives—as the basis of such fields as, say, modern electronics.) For example, if we pinpoint the position of a Ping-Pong ball with a mass of one gram to within one centimeter in any direction, then we can pinpoint its speed to an accuracy far greater than we would ever need to know. But if we measure the position of an electron to an accuracy of roughly the confines of an atom, then we cannot know its speed more precisely than about plus or minus one thousand kilometers per second, which is not very precise at all.

The limit dictated by the uncertainty principle does not depend on the way in which you try to measure the position or velocity of the particle, or on the type of particle. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is a fundamental, inescapable property of the world, and it has had profound implications for the way in which we view the world. Even after more than seventy years, these implications have not been fully appreciated by many philosophers and are still the subject of much controversy. The uncertainty principle signaled an end to Laplace’s dream of a theory of science, a model of the universe that would be completely deterministic. We certainly cannot predict future events exactly if we cannot even measure the present state of the universe precisely!

We could still imagine that there is a set of laws that determine events completely for some supernatural being who, unlike us, could observe the present state of the universe without disturbing it. However, such models of the universe are not of much interest to us ordinary mortals. It seems better to employ the principle of economy known as Occam’s razor and cut out all the features of the theory that cannot be observed. This approach led Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and Paul Dirac in the 1920s to reformulate Newton’s mechanics into a new theory called quantum mechanics, based on the uncertainty principle. In this theory, particles no longer had separate, well-defined positions and velocities. Instead, they had a quantum state, which was a combination of position and velocity defined only within the limits of the uncertainty principle.

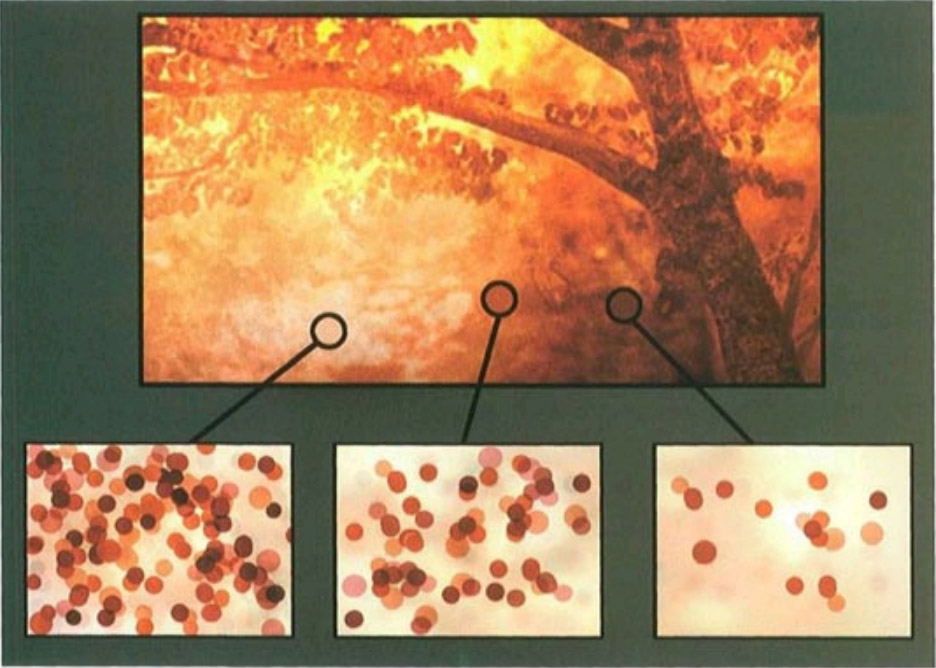

One of the revolutionary properties of quantum mechanics is that it does not predict a single definite result for an observation. Instead, it predicts a number of different possible outcomes and tells us how likely each of these is. That is to say, if you made the same measurement on a large number of similar systems, each of which started off in the same way, you would find that the result of the measurement would be A in a certain number of cases, B in a different number, and so on. You could predict the approximate number of times that the result would be A or B, but you could not predict the specific result of an individual measurement.

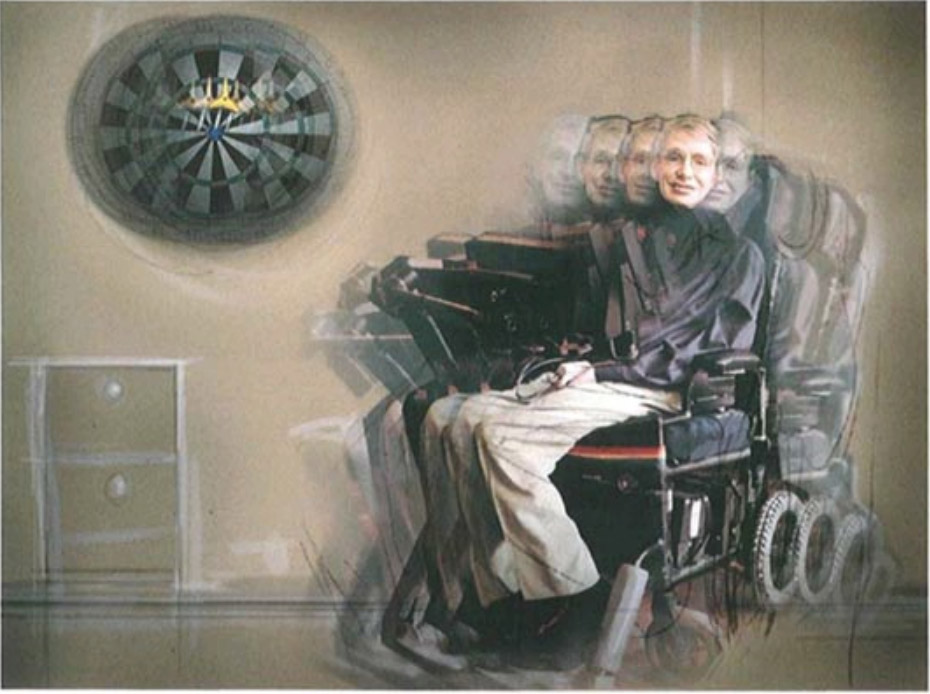

For instance, imagine you toss a dart toward a dartboard. According to classical theories—that is, the old, nonquantum theories—the dart will either hit the bull’s-eye or it will miss it. And if you know the velocity of the dart when you toss it, the pull of gravity, and other such factors, you’ll be able to calculate whether it will hit or miss. But quantum theory tells us this is wrong, that you cannot say it for certain. Instead, according to quantum theory there is a certain probability that the dart will hit the bull’s-eye, and also a nonzero probability that it will land in any other given area of the board. Given an object as large as a dart, if the classical theory—in this case Newton’s laws—says the dart will hit the bull’s-eye, then you can be safe in assuming it will. At least, the chances that it won’t (according to quantum theory) are so small that if you went on tossing the dart in exactly the same manner until the end of the universe, it is probable that you would still never observe the dart missing its target. But on the atomic scale, matters are different. A dart made of a single atom might have a 90 percent probability of hitting the bull’s-eye, with a 5 percent chance of hitting elsewhere on the board, and another 5 percent chance of missing it completely. You cannot say in advance which of these it will be. All you can say is that if you repeat the experiment many times, you can expect that, on average, ninety times out of each hundred times you repeat the experiment, the dart will hit the bull’s-eye.

Quantum mechanics therefore introduces an unavoidable element of unpredictability or randomness into science. Einstein objected to this very strongly, despite the important role he had played in the development of these ideas. In fact, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contribution to quantum theory. Nevertheless, he never accepted that the universe was governed by chance; his feelings were summed up in his famous statement "God does not play dice."

The test of a scientific theory, as we have said, is its ability to predict the results of an experiment. Quantum theory limits our abilities. Does this mean quantum theory limits science? If science is to progress, the way we carry it on must be dictated by nature. In this case, nature requires that we redefine what we mean by prediction: We may not be able to predict the outcome of an experiment exactly, but we can repeat the experiment many times and confirm that the various possible outcomes occur within the probabilities predicted by quantum theory. Despite the uncertainty principle, therefore, there is no need to give up on the belief in a world governed by physical law. In tact, in the end, most scientists were willing to accept quantum mechanics precisely because it agreed perfectly with experiment.

One of the most important implications of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is that particles behave in some respects like waves. As we have seen, they do not have a definite position but are "smeared out" with a certain probability distribution. Equally, although light is made up of waves, Planck’s quantum hypothesis also tells us that in some ways light behaves as if it were composed of particles: it can be emitted or absorbed only in packets, or quanta. In fact, the theory of quantum mechanics is based on an entirely new type of mathematics that no longer describes the real world in terms of either particles or waves. For some purposes it is helpful to think of particles as waves and for other purposes it is better to think of waves as particles, but these ways of thinking are just conveniences. This is what physicists mean when they say there is a duality between waves and particles in quantum mechanics.

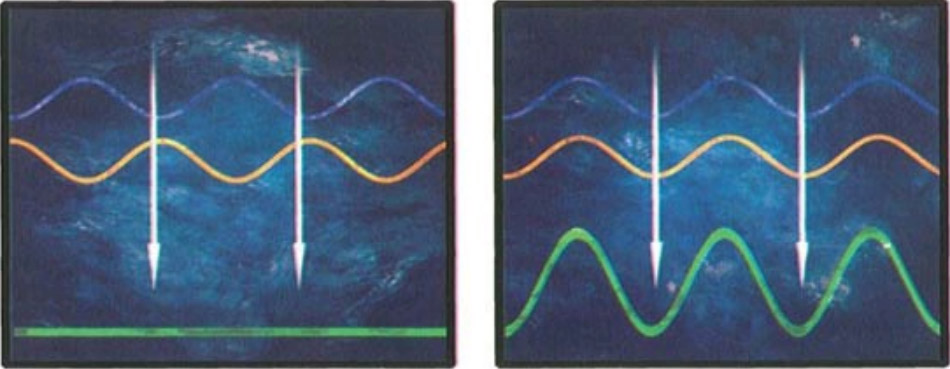

An important consequence of wavelike behavior in quantum mechanics is that one can observe what is called interference between two sets of particles. Normally, interference is thought of as a phenomenon of waves; that is to say, when waves collide, the crests of one set of waves may coincide with the troughs of the other set, in which case the waves are said to be out of phase. If that happens, the two sets of waves then cancel each other out, rather than adding up to a stronger wave, as one might expect. A familiar example of interference in the case of light is the colors that are often seen in soap bubbles. These are caused by reflection of light from the two sides of the thin film of water forming the bubble. White light consists of light waves of all different wavelengths, or colors. For certain wavelengths the crests of the waves reflected from one side of the soap film coincide with the troughs reflected from the other side. The colors corresponding to these wavelengths are absent from the reflected light, which therefore appears to be colored.

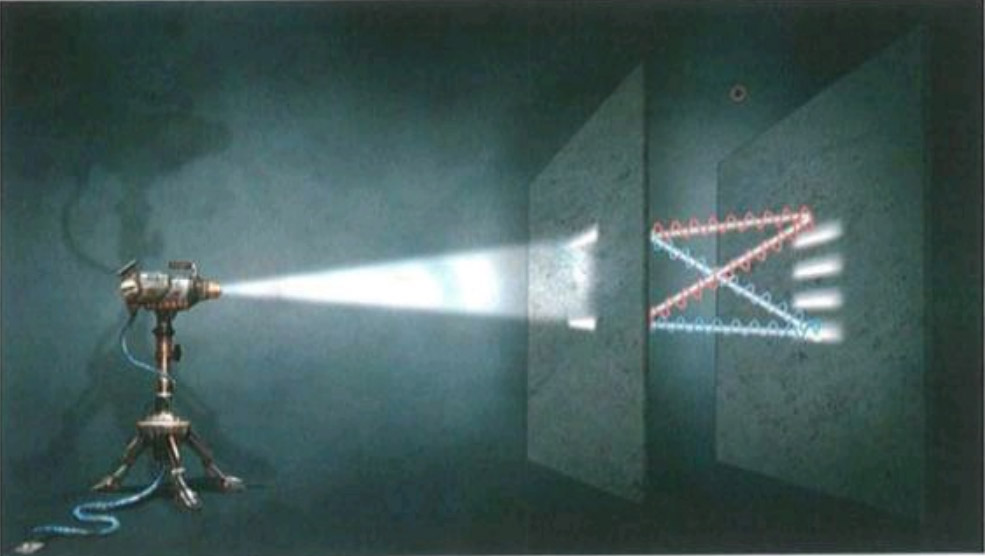

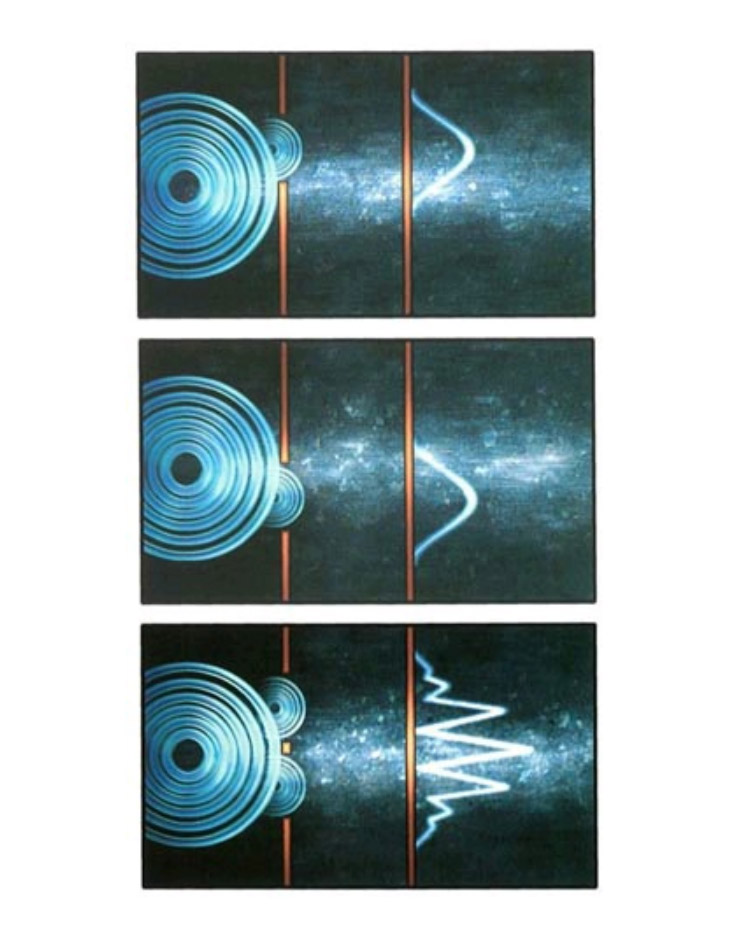

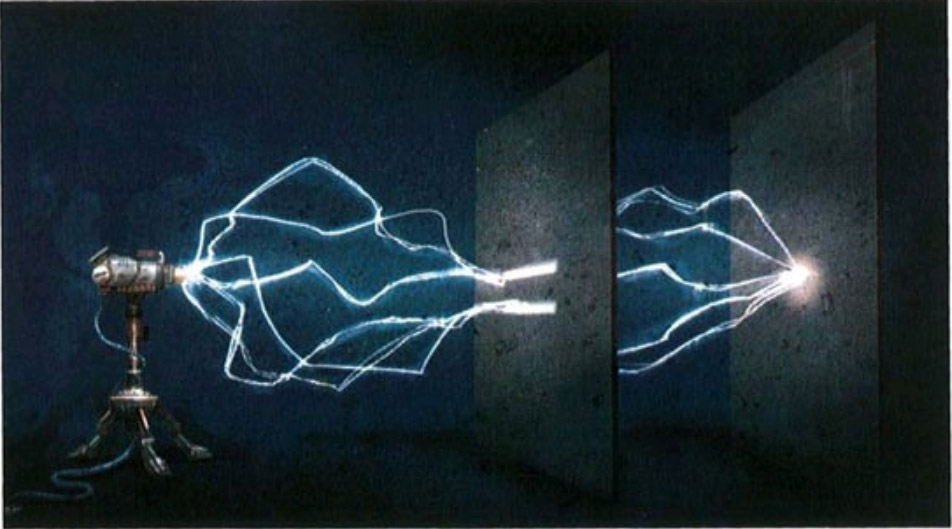

But quantum theory tells us that interference can also occur for particles, because of the duality introduced by quantum mechanics. A famous example is the so-called two-slit experiment. Imagine a partition—a thin wall—with two narrow parallel slits in it. Before we consider what happens when particles are sent through these slits, let’s examine what happens when light is shined on them. On one side of the partition you place a source of light of a particular color (that is, of a particular wavelength). Most of the light will hit the partition, but a small amount will go through the slits. Now suppose you place a screen on the far side of the partition from the light. Any point on that screen will receive waves from both slits. However, in general, the distance the light has to travel from the light source to the point via one of the slits will be different than for the light traveling via the other slit. Since the distance traveled differs, the waves from the two slits will not be in phase with each other when they arrive at the point. In some places the troughs from one wave will coincide with the crests from the other, and the waves will cancel each other out; in other places the crests and troughs will coincide, and the waves will reinforce each other; and in most places the situation will be somewhere in between. The result is a characteristic pattern of light and dark.

The remarkable thing is that you get exactly the same kind of pattern if you replace the source of light by a source of particles, such as electrons, that have a definite speed. (According to quantum theory, if the electrons have a definite speed the corresponding matter waves have a definite wavelength.) Suppose you have only one slit and start firing electrons at the partition. Most of the electrons will be stopped by the partition, but some will go through the slit and make it to the screen on the other side. It might seem logical to assume that opening a second slit in the partition would simply increase the number of electrons hitting each point of the screen. But if you open the second slit, the number of electrons hitting the screen increases at some points and decreases at others, just as if the electrons were interfering as waves do, rather than acting as particles. (See illustration on page 97.)

Now imagine sending the electrons through the slits one at a time. Is there still interference? One might expect each electron to pass through one slit or the other, doing away with the interference pattern. In reality, however, even when the electrons are sent through one at a time, the interference pattern still appears. Each electron, therefore, must be passing through both slits at the same time and interfering with itself!

The phenomenon of interference between particles has been crucial to our understanding of the structure of atoms, the basic units out of which we, and everything around us, are made. In the early twentieth century it was thought that atoms were rather like the planets orbiting the sun, with electrons (particles of negative electricity) orbiting around a central nucleus, which carried positive electricity. The attraction between the positive and negative electricity was supposed to keep the electrons in their orbits in the same way that the gravitational attraction between the sun and the planets keeps the planets in their orbits. The trouble with this was that the classical laws of mechanics and electricity, before quantum mechanics, predicted that electrons orbiting in this manner would give off radiation. This would cause them to lose energy and thus spiral inward until they collided with the nucleus. This would mean that the atom, and indeed all matter, should rapidly collapse to a state of very high density, which obviously doesn’t happen!

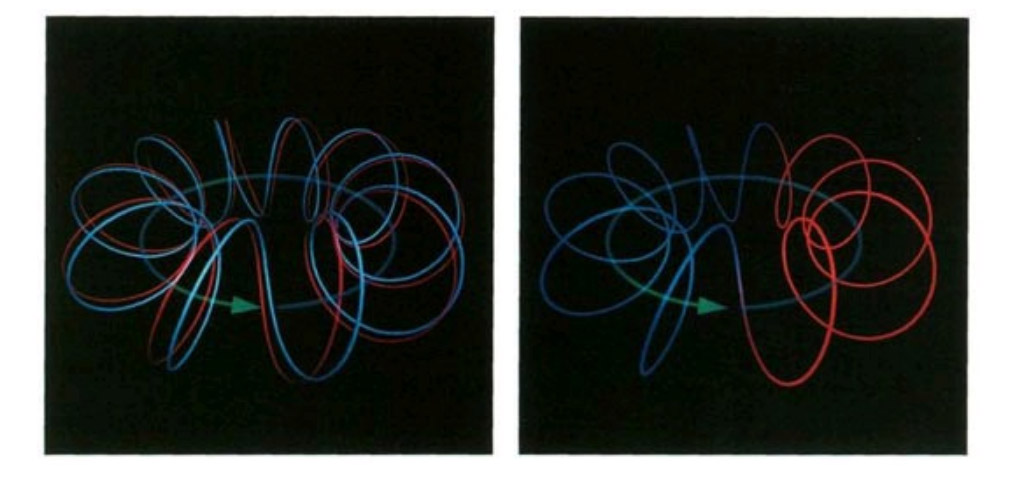

The Danish scientist Niels Bohr found a partial solution to this problem in 1913. He suggested that perhaps the electrons were not able to orbit at just am distance from the central nucleus but rather could orbit only at certain specified distances. Supposing that only one or two electrons could orbit at any one of these specified distances would solve the problem of the collapse, because once the limited number of inner orbits was full, the electrons could not spiral in any farther. This model explained quite well the structure of the simplest atom, hydrogen, which has only one electron orbiting around the nucleus. But it was not clear how to extend this model to more complicated atoms. Moreover, the idea of a limited set of allowed orbits seemed like a mere Band-Aid. It was a trick that worked mathematically, but no one knew why nature should behave that way, or what deeper law—if any—it represented. The new theory of quantum mechanics resolved this difficulty. It revealed that an electron orbiting around the nucleus could be thought of as a wave, with a wavelength that depended on its velocity. Imagine the wave circling the nucleus at specified distances, as Bohr had postulated. For certain orbits, the circumference of the orbit would correspond to a whole number (as opposed to a fractional number) of wavelengths of the electron. For these orbits the wave crest would be in the same position each time round, so the waves would reinforce each other. These orbits would correspond to Bohr’s allowed orbits. However, for orbits whose lengths were not a whole number of wavelengths, each wave crest would eventually be canceled out by a trough as the electrons went round. These orbits would not be allowed. Bohr’s law of allowed and forbidden orbits now had an explanation.

A nice way of visualizing the wave/particle duality is the so-called sum over histories introduced by the American scientist Richard Feynman. In this approach a particle is not supposed to have a single history or path in space-time, as it would in a classical, nonquantum theory. Instead it is supposed to go from point A to point B by every possible path. With each path between A and B, Feynman associated a couple of numbers. One represents the amplitude, or size, of a wave. The other represents the phase, or position in the cycle (that is, whether it is at a crest or a trough or somewhere in between). The probability of a particle going from A to B is found by adding up the waves for all the paths connecting A and B. In general, if one compares a set of neighboring paths, the phases or positions in the cycle will differ greatly. This means that the waves associated with these paths will almost exactly cancel each other out. However, for some sets of neighboring paths the phase will not vary much between paths, and the waves for these paths will not cancel out. Such paths correspond to Bohr’s allowed orbits.

With these ideas in concrete mathematical form, it was relatively straightforward to calculate the allowed orbits in more complicated atoms and even in molecules, which are made up of a number of atoms held together by electrons in orbits that go around more than one nucleus. Since the structure of molecules and their reactions with each other underlie all of chemistry and biology, quantum mechanics allows us in principle to predict nearly everything we see around us, within the limits set by the uncertainty principle. (In practice, however, we cannot solve the equations for any atom besides the simplest one, hydrogen, which has only one electron, and we use approximations and computers to analyze more complicated atoms and molecules.)

Quantum theory has been an outstandingly successful theory and underlies nearly all of modern science and technology. It governs the behavior of transistors and integrated circuits, which are the essential components of electronic devices such as televisions and computers, and it is also the basis of modern chemistry and biology. The only areas of physical science into which quantum mechanics has not yet been properly incorporated are gravity and the large-scale structure of the universe: Einstein’s general theory of relativity, as noted earlier, does not take account of the uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics, as it should for consistency with other theories.

As we saw in the last chapter, we already know that general relativity must be altered. By predicting points of infinite density—singularities—classical (that is, nonquantum) general relativity predicts its own downfall, just as classical mechanics predicted its downfall by suggesting that blackbodies should radiate infinite energy or that atoms should collapse to infinite density. And as with classical mechanics, we hope to eliminate these unacceptable singularities by making classical general relativity into a quantum theory—that is, by creating a quantum theory of gravity.

If general relativity is wrong, why have all experiments thus far supported it? The reason that we haven’t yet noticed am discrepancy with observation is that all the gravitational fields that we normally experience are very weak. But as we have seen, the gravitational field should get very strong when all the matter and energy in the universe are squeezed into a small volume in the early universe. In the presence of such strong fields, the effects of quantum theory should be important.

Although we do not yet possess a quantum theory of gravity, w e do know a number of features we believe it should have. One is that it should incorporate Feynman’s proposal to formulate quantum theory in terms of a sum over histories. A second feature that we believe must be part of any ultimate theory is Einstein’s idea that the gravitational field is represented by curved space-time: particles try to follow the nearest thing to a straight path in a curved space, but because space-time is not flat, their paths appear to be bent, as if by a gravitational field. When we apply Feynman’s sum over histories to Einstein’s view of gravity, the analogue of the history of a particle is now a complete curved space-time that represents the history of the whole universe.

In the classical theory of gravity, there are only two possible ways the universe can behave: either it has existed for an infinite time, or else it had a beginning at a singularity at some finite time in the past. For reasons we discussed earlier, we believe that the universe has not existed forever. Yet if it had a beginning, according to classical general relativity, in order to know which solution of Einstein’s equations describes our universe, we must know its initial state—that is, exactly how the universe began. God may have originally decreed the laws of nature, but it appears that He has since left the universe to evolve according to them and does not now intervene in it. How did He choose the initial state or configuration of the universe? What were the boundary conditions at the beginning of time? In classical general relativity this is a problem, because classical general relativity breaks down at the beginning of the universe.

In the quantum theory of gravity, on the other hand, a new possibility arises that, if true, would remedy this problem. In the quantum theory, it is possible for space-time to be finite in extent and yet to have no singularities that formed a boundary or edge. Space-time would be like the surface of the earth, only with two more dimensions. As was pointed out before, if you keep traveling in a certain direction on the surface of the earth, you never come up against an impassable barrier or fall over the edge, but eventually come back to where you started, without running into a singularity. So if this turns out to be the case, then the quantum theory of gravity has opened up a new possibility in w hich there would be no singularities at w hich the laws of science broke down.

If there is no boundary to space-time, there is no need to specify the behavior at the boundary—no need to know the initial state of the universe. There is no edge of space-time at which we would have to appeal to God or some new law to set the boundary conditions for space-time. We could say: "The boundary condition of the universe is that it has no boundary." The universe would be completely self-contained and not affected by anything outside itself. It would neither be created nor destroyed. It would just BE. As long as we believed the universe had a beginning, the role of a creator seemed clear. But if the universe is really completely self-contained, having no boundary or edge, having neither beginning nor end, then the answer is not so obvious: what is the role of a creator?

Contents

-

Chapter 1

Thinking about the universe

-

Chapter 2

Our evolving picture of the universe

-

Chapter 3

The nature of a scientific theory

-

Chapter 4

Newton's Universe

-

Chapter 5

Relativity

-

Chapter 6

Curved Space

-

Chapter 7

The expanding Universe

-

Chapter 8

The big bang, black holes, and the evolution of the universe

-

Chapter 9

Quantum Gravity

-

Chapter 10

Wormholes and time travel

-

Chapter 11

The forces of nature and the unification of physics

-

Chapter 12

Conclusion