Wormholes and Time Travel

In previous chapters we have seen how our views of the nature of time have changed over the years. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, people believed in an absolute time. That is, each event could be labeled by a number called "time" in a unique way, and all good clocks would agree on the time interval between two events. However, the discovery that the speed of light appeared the same to every observer, no matter how he was moving, led to the theory of relativity— and the abandoning of the idea that there was a unique absolute time. The time of events could not be labeled in a unique way. Instead, each observer would have his own measure of time as recorded by a clock that he carried, and clocks carried by different observers would not necessarily agree. Thus time became a more personal concept, relative to the observer who measured it. Still, time was treated as if it were a straight railway line on which you could go only one way or the other. But what if the railway line had loops and branches, so a train could keep going forward but come back to a station it had already passed? In other words, might it be possible for someone to travel into the future or the past? H. G. Wells in The Time Machine explored these possibilities, as have countless other writers of science fiction. Yet many of the ideas of science fiction, like submarines and travel to the moon, have become matters of science fact. So what are the prospects for time travel?

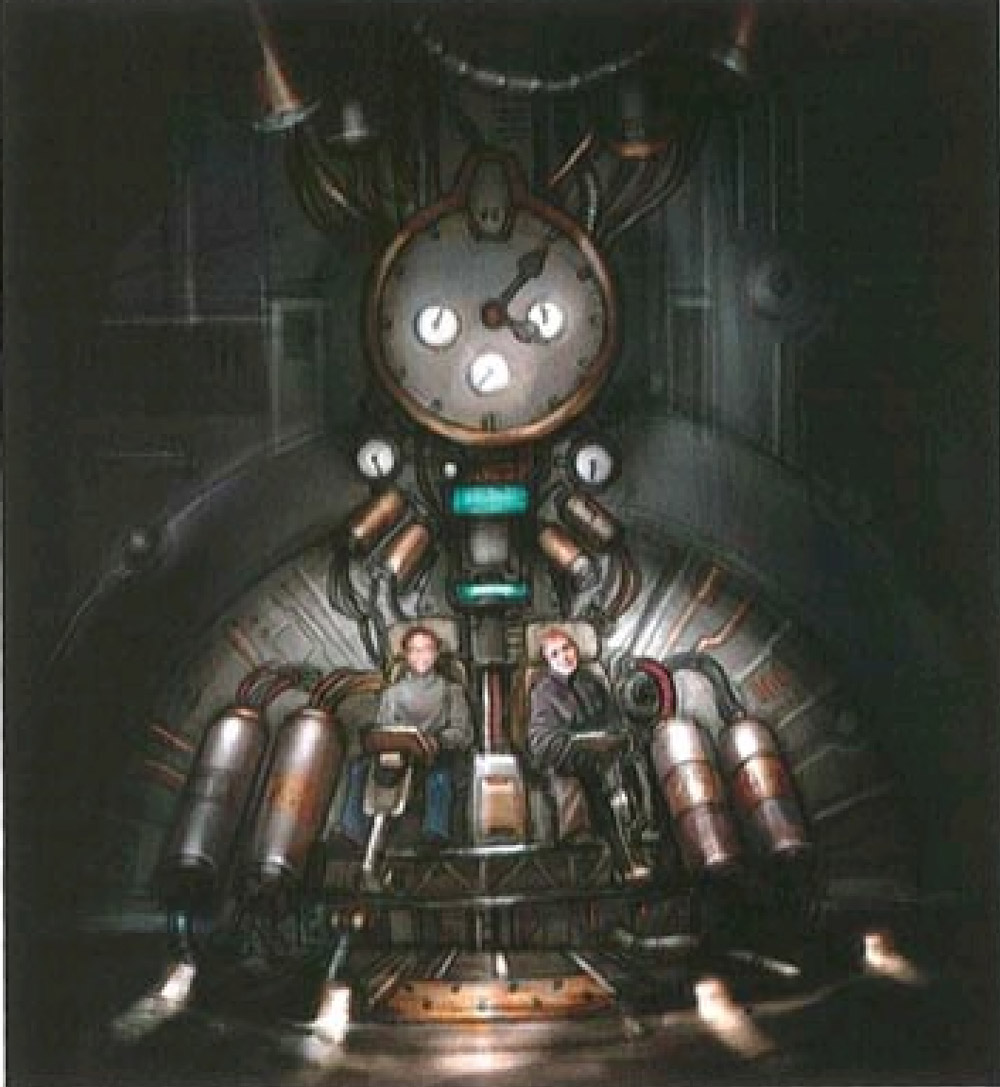

It is possible to travel to the future. That is, relativity shows that it is possible to create a time machine that will jump you forward in time. You step into the time machine, wait, step out, and find that much more time has passed on the earth than has passed for you. We do not have the technology today to do this, but it is just a matter of engineering: we know it can be done. One method of building such a machine would be to exploit the situation we discussed in Chapter 6 regarding the twins paradox. In this method, while you are sitting in the time machine, it blasts off, accelerating to nearly the speed of light, continues for a while (depending upon how far forward in time you wish to travel), and then returns. It shouldn’t surprise you that the time machine is also a spaceship, because according to relativity, time and space are related. In any case, as far as you are concerned, the only "place" you will be during the whole process is inside the time machine. And when you step out, you will find that more time has passed on the earth than has gone by for you. You have traveled to the future. But can you go back? Can we create the conditions necessary to travel backward in time?

The first indication that the laws of physics might really allow people to travel backward in time came in 1949 when Kurt Gödel discovered a new solution to Einstein’s equations; that is, a new space-time allowed by the theory of general relativity. Many different mathematical models of the universe satisfy Einstein’s equations, but that doesn’t mean they correspond to the universe we live in. They differ, for instance, in their initial or boundary conditions. We must check the physical predictions of these models in order to decide whether or not they might correspond to our universe.

Gödel was a mathematician who was famous for proving that it is impossible to prove all true statements, even if you limit yourself to trying to prove all the true statements in a subject as apparently cut-and-dried as arithmetic. Like the uncertainty principle, Gödel’s incompleteness theorem may be a fundamental limitation on our ability to understand and predict the universe. Gödel got to know about general relativity when he and Einstein spent their later years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Gödel’s space-time had the curious property that the whole universe was rotating.

What does it mean to say that the whole universe is rotating? To rotate means to turn around and around, but doesn’t that imply the existence of a stationary point of reference? So you might ask, "Rotating with respect to what?" The answer is a bit technical, but it is basically that distant matter would be rotating with respect to directions that little tops or gyroscopes point in within the universe. In Gödel’s space-time, a mathematical side effect of this was that if you traveled a great distance away from earth and then returned, it would be possible to get back to earth before you set out.

That his equations might allow this possibility really upset Einstein, who had thought that general relativity wouldn’t allow time travel. But although it satisfies Einstein’s equations, the solution Gödel found doesn’t correspond to the universe we live in because our observations show that our universe is not rotating, at least not noticeably. Nor does Gödel’s universe expand, as ours does. However, since then, scientists studying Einstein’s equations have found other space-times allowed by general relativity that do permit travel into the past. Yet observations of the microwave background and of the abundances of elements such as hydrogen and helium indicate that the early universe did not have the kind of curvature these models require in order to allow time travel. The same conclusion follows on theoretical grounds if the no-boundary proposal is correct. So the question is this: if the universe starts out without the kind of curvature required for time travel, can we subsequently warp local regions of space-time sufficiently to allow it?

Again, since time and space are related, it might not surprise you that a problem closely related to the question of travel backward in time is the question of whether or not you can travel faster than light. That time travel implies faster-than-light travel is easy to see: by making the last phase of your trip a journey backward in time, you can make your overall trip in as little time as you wish, so you’d be able to travel with unlimited speed! But, as we’ll see, it also works the other way: if you can travel with unlimited speed, you can also travel backward in time. One cannot be possible without the other.

The issue of faster-than-light travel is a problem of much concern to writers of science fiction. Their problem is that, according to relativity, if we sent a spaceship to our nearest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri, which is about four light-years away, it would take at least eight years before we could expect the travelers to return and tell us what they had found. And if the expedition were to the center of our galaxy, it would be at least a hundred thousand years before it came back. Not a good situation if you want to write about intergalactic warfare! Still, the theory of relativity does allow one consolation, again along the lines of our discussion of the twins paradox in Chapter 6: it is possible for the journey to seem to be much shorter for the space travelers than for those who remain on earth. But there would not be much joy in returning from a space voyage a few years older to find that everyone you had left behind was dead and gone thousands of years ago. So in order to have any human interest in their stories, science fiction writers had to suppose that we would one day discover how to travel faster than light. Most of these authors don’t seem to have realized the fact that if you can travel faster than light, the theory of relativity implies you can also travel back in time, as the following limerick says:

There was a young lady of Wight

Who traveled much faster than light

She departed one day,

In a relative way,

And arrived on the previous night

The key to this connection is that the theory of relativity says not only that there is no unique measure of time on which all observers will agree but that, under certain circumstances, observers need not even agree on the order of events. In particular, if two events, A and B, are so far away in space that a rocket must travel faster than the speed of light to get from event A to event B, then two observers moving at different speeds can disagree on whether event A occurred before B, or event B occurred before event A. Suppose, for instance, that event A is the finish of the final hundred-meter race of the Olympic Games in 2012 and event B is the opening of the 100,004th meeting of the Congress of Proxima Centauri. Suppose that to an observer on Earth, event A happened first, and then event B. Let’s say that B happened a year later, in 2013 by Earth’s time. Since the earth and Proxima Centauri are some four light-years apart, these two events satisfy the above criterion: though A happens before B, to get from A to B you would have to travel faster than light. Then, to an observer on Proxima Centauri moving away from the earth at nearly the speed of light, it would appear that the order of the events is reversed: it appears that event B occurred before event A. This observer would say it is possible, if you could move faster than light, to get from event B to event A. In fact, if you went really fast, you could also get back from A to Proxima Centauri before the race and place a bet on it in the sure knowledge of who would win!

There is a problem with breaking the speed-of-light barrier. The theory of relativity says that the rocket power needed to accelerate a spaceship gets greater and greater the nearer it gets to the speed of light. We have experimental evidence for this, not with spaceships but with elementary particles in particle accelerator such as those at Fermilab or the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN). We can accelerate particles to 99.99 percent of the speed of light, but however much power we feed in, we can’t get them beyond the speed-of-light barrier. Similarly with spaceships: no matter how much rocket power they have, they can’t accelerate beyond the speed of light. And since travel backward in time is possible only if faster-than-light travel is possible, this might seem to rule out both rapid space travel and travel back in time.

However, there is a possible way out. It might be that you could warp space-time so that there was a shortcut between A and B. One way of doing this would be to create a wormhole between A and B. As its name suggests, a wormhole is a thin tube of space-time that can connect two nearly flat regions far apart. It is somewhat like being at the base of a high ridge of mountains. To get to the other side, you would normally have to climb a long distance up and then back down—but not if there was a giant wormhole that cut horizontally through the rock. You could imagine creating or finding a wormhole that would lead from the vicinity of our solar system to Proxima Centauri. The distance through the wormhole might be only a few million miles, even though the earth and Proxima Centauri are twenty million million miles apart in ordinary space. If we transmit the news of the hundred-meter race through the wormhole, there could be plenty of time for it to get there before the opening of the Congress. But then an observer moving toward the earth should also be able to find another wormhole that would enable him to get from the opening of the Congress on Proxima Centauri back to the earth before the start of the race. So wormholes, like any other possible form of travel faster than light, would allow you to travel into the past.

The idea of wormholes between different regions of space-time is not an invention of science fiction writers; it came from a very respectable source. In 1935, Einstein and Nathan Rosen wrote a paper in which they showed that general relativity allowed what then called bridges, but which are now known as wormholes. The Einstein-Rosen bridges didn’t last long enough for a spaceship to get through: the ship would run into a singularity as the wormhole pinched off. However, it has been suggested that it might be possible for an advanced civilization to keep a wormhole open. To do this, or to warp space-time in any other way so as to permit time travel, you can show that you need a region of space-time with negative curvature, like the surface of a saddle. Ordinary matter, which has positive energy density, gives space-time a positive curvature, like the surface of a sphere. So w hat is needed in order to warp space-time in a way that will allow travel into the past is matter with negative energy density.

What does it mean to have negative energy density? Energy is a bit like money: if you have a positive balance, you can distribute it in various ways, but according to the classical laws that were believed a century ago, you weren’t allowed to have your bank account overdrawn. So these classical law s would have ruled out negative energy density and hence am possibility of travel backward in time. However, as has been described in earlier chapters, the classical laws were superseded by quantum laws based on the uncertainty principle. The quantum laws are more liberal and allow you to be overdrawn on one or two accounts provided the total balance is positive. In other words, quantum theory allows the energy density to be negative in some places, provided that this is made up for by positive energy densities in other places, so that the total energy remains positive. We thus have reason to believe both that space-time can be warped and that it can be curved in the way necessary to allow time travel.

According to the Feynman sum over histories, time travel into the past does, in a way, occur on the scale of single particles. In Feynman’s method, an ordinary particle moving forward in time is equivalent to an antiparticle moving backward in time. In his mathematics, you can regard a particle/antiparticle pair that are created together and then annihilate each other as a single particle moving on a closed loop in space-time. To see this, first picture the process in the traditional way. At a certain time—say, time A—a particle and antiparticle are created. Both move forward in time. Then, at a later time, time B, they interact again, and annihilate each other. Before A and after B, neither particle exists. According to Feynman, though, you can look at this differently. At A, a single particle is created. It moves forward in time to B, then it returns back in time to A. Instead of a particle and antiparticle moving forward in time together, there is just a single object moving in a "loop" from A to B and back again. When the object is moving forward in time (from A to B), it is called a particle. But when the object is traveling back in time (from B to A), it appears as an antiparticle traveling forward in time.

Such time travel can produce observable effects. For instance, suppose that one member of the particle/antiparticle pair (say, the antiparticle) falls into a black hole, leaving the other member without a partner with which to annihilate. The forsaken particle might fall into the hole as well, but it might also escape from the vicinity of the black hole. If so, to an observer at a distance it would appear to be a particle emitted by the black hole. You can, however, have a different but equivalent intuitive picture of the mechanism for emission of radiation from black holes. You can regard the member of the pair that fell into the black hole (say, the antiparticle) as a particle traveling backward in time out of the hole. When it gets to the point at which the particle/antiparticle pair appeared together, it is scattered by the gravitational field of the black hole into a particle traveling forward in time and escaping from the black hole. Or if instead it was the particle member of the pair that fell into the hole, you could regard it as an antiparticle traveling back in time and coming out of the black hole. Thus the radiation by black holes shows that quantum theory allows time travel back in time on a microscopic scale.

We can therefore ask whether quantum theory allows the possibility that, once we advance in science and technology, we might eventually manage to build a time machine. At first sight, it seems it should be possible. The Feynman sum over histories proposal is supposed to be over all histories. Thus it should include histories in which space-time is so warped that it is possible to travel into the past. Yet even if the known laws of physics do not seem to rule out time travel, there are other reasons to question whether it is possible.

One question is this: if it’s possible to travel into the past, why hasn’t anyone come back from the future and told us how to do it? There might be good reasons why it would be unwise to give us the secret of time travel at our present primitive state of development, but unless human nature changes radically, it is difficult to believe that some visitor from the future wouldn’t spill the beans. Of course, some people would claim that sightings of UFOs are evidence that we are being visited either by aliens or by people from the future. (Given the great distance of other stars, if the aliens were to get here in reasonable time, they would need faster-than-light travel, so the two possibilities may be equivalent.) A possible way to explain the absence of visitors from the future would be to say that the past is fixed because we have observed it and seen that it does not have the kind of warping needed to allow travel back from the future. On the other hand, the future is unknown and open, so it might well have the curvature required. This would mean that any time travel would be confined to the future. There would be no chance of Captain Kirk and the starship Enterprise turning up at the present time.

This might explain why we have not yet been overrun by tourists from the future, but it would not avoid another type of problem, which arises if it is possible to go back and change history: why aren’t we in trouble with history? Suppose, for example, someone had gone back and given the Nazis the secret of the atom bomb, or that you went back and killed your great-great-grandfather before he had children. There are many versions of this paradox, but they are essentially equivalent: we would get contradictions if we were free to change the past.

There seem to be two possible resolutions to the paradoxes posed by time travel. The first may be called the consistent histories approach. It says that even if space-time is warped so that it would be possible to travel into the past, what happens in space-time must be a consistent solution of the laws of physics. In other words, according to this viewpoint, you could not go back in time unless history already showed that you had gone back and, while there, had not killed your great-great-grandfather or committed any other acts that would conflict with the history of how you got to your current situation in the present. Moreover, when you did go back, you wouldn’t be able to change recorded history; you would merely be following it. In this view the past and future are preordained: you would not have free will to do what you wanted.

Of course, you could say that free will is an illusion anyway. If there really is a complete theory of physics that governs everything, it presumably also determines your actions. But it does so in a way that is impossible to calculate for an organism that is as complicated as a human being, and it involves a certain randomness due to quantum mechanical effects. So one way to look at it is that we say humans have free will because we can’t predict what they will do. However, if a human then goes off in a rocket ship and comes back before he set off, we will be able to predict what he will do because it will be part of recorded history. Thus, in that situation, the time traveler would not in any sense have free will.

The other possible way to resolve the paradoxes of time travel might be called the alternative histories hypothesis. The idea here is that when time travelers go back to the past, they enter alternative histories that differ from recorded history. Thus they can act freely, without the constraint of consistency with their previous history. Steven Spielberg had fun with this notion in the Back to the Future films: Marty McFly was able to go back and change his parents’ courtship to a more satisfactory history.

The alternative histories hypothesis sounds rather like Richard Feynman’s way of expressing quantum theory as a sum over histories, as described in Chapter 9. This said that the universe didn’t just have a single history; rather, it had every possible history, each with its own probability. However, there seems to be an important difference between Feynman’s proposal and alternative histories. In Feynman’s sum, each history comprises a complete space-time and everything in it. The space-time may be so warped that it is possible to travel in a rocket into the past. But the rocket would remain in the same space-time and therefore the same history, which would have to be consistent. Thus, Feynman’s sum over histories proposal seems to support the consistent histories hypothesis rather than the idea of alternative histories.

We can avoid these problems if we adopt what we might call the chronology protection conjecture. This says that the laws of physics conspire to prevent macroscopic bodies from carrying information into the past. This conjecture has not been proved, but there is reason to believe it is true. The reason is that when space-time is warped enough to make time travel into the past possible, calculations employing quantum theory show that particle/antiparticle pairs moving round and round on closed loops can create energy densities large enough to give space-time a positive curvature, counteracting the warpage that allows the time travel. Because it is not yet clear whether this is so, the possibility of time travel remains open. But don’t bet on it. Your opponent might have the unfair advantage of knowing the future.

Contents

-

Chapter 1

Thinking about the universe

-

Chapter 2

Our evolving picture of the universe

-

Chapter 3

The nature of a scientific theory

-

Chapter 4

Newton's Universe

-

Chapter 5

Relativity

-

Chapter 6

Curved Space

-

Chapter 7

The expanding Universe

-

Chapter 8

The big bang, black holes, and the evolution of the universe

-

Chapter 9

Quantum Gravity

-

Chapter 10

Wormholes and time travel

-

Chapter 11

The forces of nature and the unification of physics

-

Chapter 12

Conclusion