The Big Bang, Black Holes, and the evolution of the Universe

In Friedmann's first model of the universe, the fourth dimension, time—like space—is finite in extent. It is like a line with two ends, or boundaries. So time has an end, and it also has a beginning. In fact, all solutions to Einstein’s equations in which the universe has the amount of matter we observe share one very important feature: at some time in the past (about 13.7 billion years ago), the distance between neighboring galaxies must have been zero. In other words, the entire universe was squashed into a single point with zero size, like a sphere of radius zero. At that time, the density of the universe and the curvature of space-time would have been infinite. It is the time that we call the big bang.

All our theories of cosmology are formulated on the assumption that space-time is smooth and nearly flat. That means that all our theories break down at the big bang: a space-time with infinite curvature can hardly be called nearly flat! Thus even if there were events before the big bang, we could not use them to determine what would happen afterward, because predictability would have broken down at the big bang.

Correspondingly, if, as is the case, we know only what has happened since the big bang, we cannot determine what happened beforehand. As far as we are concerned, events before the big bang can have no consequences and so should not form part of a scientific model of the universe. We should therefore cut them out of the model and say that the big bang was the beginning of time. This means that questions such as who set up the conditions for the big bang are not questions that science addresses.

Another infinity that arises if the universe has zero size is in temperature. At the big bang itself, the universe is thought to have been infinitely hot. As the universe expanded, the temperature of the radiation decreased. Since temperature is simply a measure of the average energy—or speed—of particles, this cooling of the universe would have a major effect on the matter in it. At very high temperatures, particles would be moving around so fast that they could escape any attraction toward each other resulting from nuclear or electromagnetic forces, but as they cooled off, we would expect particles that attract each other to start to clump together. Even the types of particles that exist in the universe depend on the temperature, and hence on the age, of the universe.

Aristotle did not believe that matter was made of particles. He believed that matter was continuous. That is, according to him, a piece of matter could be divided into smaller and smaller bits without any limit: there could never be a grain of matter that could not be divided further. A few Greeks, however, such as Democritus, held that matter was inherently grainy and that everything was made up of large numbers of various different kinds of atoms. (The word atom means "indivisible" in Greek.) We now know that this is true—at least in our environment, and in the present state of the universe. But the atoms of our universe did not always exist, they are not indivisible, and they represent only a small fraction of the types of particles in the universe

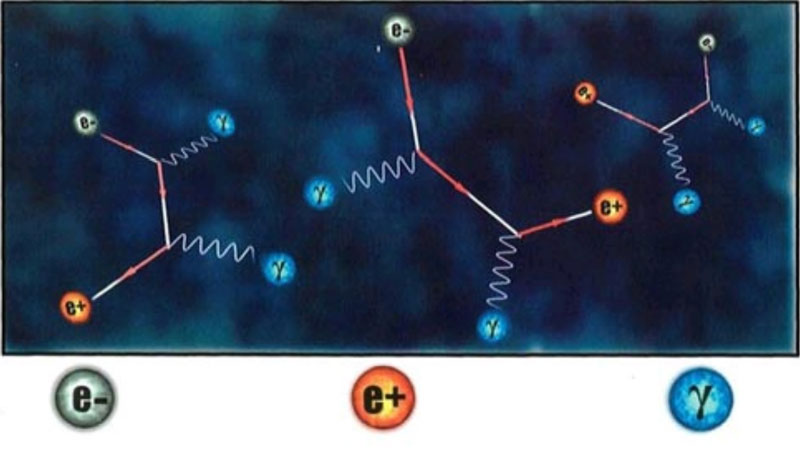

Atoms are made of smaller particles: electrons, protons, and neutrons. The protons and neutrons themselves are made of yet smaller particles called quarks. In addition, corresponding to each of these subatomic particles there exists an antiparticle. Antiparticles have the same mass as their sibling particles but are opposite in their charge and other attributes. For instance, the antiparticle for an electron, called a positron, has a positive charge, the opposite of the charge of the electron. There could be whole antiworlds and antipeople made out of antiparticles. However, when an antiparticle and particle meet, they annihilate each other. So if you meet your antiself, don’t shake hands—you would both vanish in a great flash of light!

Light energy comes in the form of another type of particle, a massless particle called a photon. The nearby nuclear furnace of the sun is the greatest source of photons for the earth. The sun is also a huge source of another kind of particle, the aforementioned neutrino (and antineutrino). But these extremely light particles hardly ever interact with matter, and hence they pass through us without effect, at a rate of billions each second. All told, physicists have discovered dozens of these elementary particles. Over time, as the universe has undergone a complex evolution, the makeup of this zoo of particles has also evolved. It is this evolution that has made it possible for planets such as the earth, and beings such as we, to exist.

One second after the big bang, the universe would have expanded enough to bring its temperature down to about ten billion degrees Celsius. This is about a thousand times the temperature at the center of the sun, but temperatures as high as this are reached in H-bomb explosions. At this time the universe would have contained mostly photons, electrons, and neutrinos, and their antiparticles, together with some protons and neutrons. These particles would have had so much energy that when they collided, they would have produced many different particle/antiparticle pairs. For instance, colliding photons might produce an electron and its antiparticle, the positron. Some of these newly produced particles would collide with an antiparticle sibling and be annihilated. Any time an electron meets up with a positron, both will be annihilated, but the reverse process is not so easy: in order for two massless particles such as photons to create a particle/antiparticle pair such as an electron and a positron, the colliding massless particles must have a certain minimum energy. That is because an electron and positron have mass, and this newly created mass must come from the energy of the colliding particles. As the universe continued to expand and the temperature to drop, collisions having enough energy to create electron/positron pairs would occur less often than the rate at which the pairs were being destroyed by annihilation. So eventually most of the electrons and positrons would have annihilated each other to produce more photons, leaving only relatively few electrons. The neutrinos and antineutrinos, on the other hand, interact with themselves and with other particles only very weakly, so they would not annihilate each other nearly as quickly. They should still be around today. If we could observe them, it would provide a good test of this picture of a very hot early stage of the universe, but unfortunately, after billions of years their energies would now be too low for us to observe them directly (though we might be able to detect them indirectly).

About one hundred seconds after the big bang, the temperature of the universe would have fallen to one billion degrees, the temperature inside the hottest stars. At this temperature, a force called the strong force would have played an important role. The strong force, which we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 11, is a short-range attractive force that can cause protons and neutrons to bind to each other, forming nuclei. At high enough temperatures, protons and neutrons have enough energy of motion (see Chapter 5) that they can emerge from their collisions still free and independent. But at one billion degrees, they would no longer have had sufficient energy to overcome the attraction of the strong force, and they would have started to combine to produce the nuclei of atoms of deuterium (heavy hydrogen), which contain one proton and one neutron. The deuterium nuclei would then have combined with more protons and neutrons to make helium nuclei, which contain two protons and two neutrons, and also small amounts of a couple of heavier elements, lithium and beryllium. One can calculate that in the hot big bang model, about a quarter of the protons and neutrons would have been converted into helium nuclei, along with a small amount of heavy hydrogen and other elements. The remaining neutrons would have decayed into protons, which are the nuclei of ordinary hydrogen atoms.

This picture of a hot early stage of the universe was first put forward by the scientist George Gamow (see page 61) in a famous paper written in 1948 with a student of his, Ralph Alpher. Gamow had quite a sense of humor—he persuaded the nuclear scientist Hans Bethe to add his name to the paper to make the list of authors Alpher, Bethe, Gamow, like the first three letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha, beta, gamma, and particularly appropriate for a paper on the beginning of the universe! In this paper they made the remarkable prediction that radiation (in the form of photons) from the very hot early stages of the universe should still be around today, but with its temperature reduced to only a few degrees above 1absolute zero. (Absolute zero, -273 degrees Celsius, is the temperature at which substances contain no heat energy, and is thus the lowest possible temperature.)

It was this microwave radiation that Penzias and Wilson found in 1965. At the time that Alpher, Bethe, and Gamow wrote their paper, not much was known about the nuclear reactions of protons and neutrons. Predictions made for the proportions of various elements in the early universe were therefore rather inaccurate, but these calculations have been repeated in the light of better knowledge and now agree very well with what we observe. It is, moreover, very difficult to explain in any other way why about one-quarter of the mass of the universe is in the form of helium

But there are problems with this picture. In the hot big bang model there was not enough time in the early universe for heat to have flowed from one region to another. This means that the initial state of the universe would have to have had exactly the same temperature everywhere in order to account for the fact that the microwave background has the same temperature in every direction we look. Moreover, the initial rate of expansion would have had to be chosen very precisely for the rate of expansion still to be so close to the critical rate needed to avoid collapse. It would be very difficult to explain why the universe should have begun in just this way, except as the act of a God who intended to create beings like us. In an attempt to find a model of the universe in which many different initial configurations could have evolved to something like the present universe, a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Alan Guth, suggested that the early universe might have gone through a period of very rapid expansion. This expansion is said to be inflationary, meaning that the universe at one time expanded at an increasing rate. According to Guth, the radius of the universe increased by a million million million million million—1 with thirty zeros after it—times in only a tiny fraction of a second. Any irregularities in the universe would have been smoothed out by this expansion, just as the wrinkles in a balloon are smoothed away when you blow it up. In this way, inflation explains how the present smooth and uniform state of the universe could have evolved from many different nonuniform initial states. So we are therefore fairly confident that we have the right picture, at least going back to about one-billion-trillion-trillionth of a second after the big bang.

After all this initial turmoil, within only a few hours of the big bang, the production of helium and some other elements such as lithium would have stopped. And after that, for the next million years or so, the universe would have just continued expanding, without anything much happening. Eventually, once the temperature had dropped to a few thousand degrees and electrons and nuclei no longer had enough energy of motion to overcome the electromagnetic attraction between them, they would have started combining to form atoms. The universe as a whole would have continued expanding and cooling, but in regions that were slightly denser than average, this expansion would have been slowed down by the extra gravitational attraction.

This attraction would eventually stop expansion in some regions and cause them to start to collapse. As they were collapsing, the gravitational pull of matter outside these regions might start them rotating slightly. As the collapsing region got smaller, it would spin faster—just as skaters spinning on ice spin faster as they draw in their arms. Eventually, when the region got small enough, it would be spinning fast enough to balance the attraction of gravity, and in this way disklike rotating galaxies were born. Other regions that did not happen to pick up a rotation would become oval objects called elliptical galaxies. In these, the region would stop collapsing because individual parts of the galaxy would be orbiting stably around its center, but the galaxy would have no overall rotation.

As time went on, the hydrogen and helium gas in the galaxies would break up into smaller clouds that would collapse under their own gravity. As these contracted and the atoms within them collided with one another, the temperature of the gas would increase, until eventually it became hot enough to start nuclear fusion reactions. These would convert the hydrogen into more helium. The heat released in this reaction, which is like a controlled hydrogen bomb explosion, is what makes a star shine. This additional heat also increases the pressure of the gas until it is sufficient to balance the gravitational attraction, and the gas stops contracting. In this manner, these clouds coalesce into stars like our sun, burning hydrogen into helium and radiating the resulting energy as heat and light. It is a bit like a balloon—there is a balance between the pressure of the air inside, which is trying to make the balloon expand, and the tension in the rubber, which is trying to make the balloon smaller.

Once clouds of hot gas coalesce into stars, the stars will remain stable for a long time, with heat from the nuclear reactions balancing the gravitational attraction. Eventually, however, the star will run out of its hydrogen and other nuclear fuels. Paradoxically, the more fuel a star starts off with, the sooner it runs out. This is because the more massive the star is, the hotter it needs to be to balance its gravitational attraction. And the hotter the star, the faster the nuclear fusion reaction and the sooner it will use up its fuel. Our sun has probably got enough fuel to last another five billion years or so, but more massive stars can use up their fuel in as little as one hundred million years, much less than the age of the universe.

When a star runs out of fuel, it starts to cool off and gravity takes over, causing it to contract. This contraction squeezes the atoms together and causes the star to become hotter again. As the star heats up further, it would start to convert helium into heavier elements such as carbon or oxygen. This, however, would not release much more energy, so a crisis would occur. What happens next is not completely clear, but it seems likely that the central regions of the star would collapse to a very dense state, such as a black hole. The term "black hole" is of very recent origin. It was coined in 1969 by the American scientist John Wheeler as a graphic description of an idea that goes back at least two hundred years, to a time when there were two theories about light: one, which Newton favored, was that it was composed of particles, and the other was that it was made of waves. We now know that actually, both theories are correct. As we will see in Chapter 9, by the wave/particle duality of quantum mechanics, light can be regarded as both a wave and a particle. The descriptors wave and particle are concepts humans created, not necessarily concepts that nature is obliged to respect by making all phenomena fall into one category or the other!

Under the theory that light is made up of waves, it was not clear how it would respond to gravity. But if we think of light as being composed of particles, we might expect those particles to be affected by gravity in the same way that cannonballs, rockets, and planets are. In particular, if you shoot a cannonball upward from the surface of the earth—or a star—like the rocket on page 58, it will eventually stop and then fall back unless the speed with which it starts upward exceeds a certain value. This minimum speed is called the escape velocity. The escape velocity of a star depends on the strength of its gravitational pull. The more massive the star, the greater its escape velocity. At first people thought that particles of light traveled infinitely fast, so gravity would not have been able to slow them down, but the discovery by Roemer that light travels at a finite speed meant that gravity might have an important effect: if the star is massive enough, the speed of light will be less than the star’s escape velocity, and all light emitted by the star will fall back into it. On this assumption, in 1783 a Cambridge don, John Michell, published a paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in which he pointed out that a star that was sufficiently massive and compact would have such a strong gravitational field that light could not escape: any light emitted from the surface of the star would be dragged back by the star’s gravitational attraction before it could get very far. Such objects are what we now call black holes, because that is what they are: black voids in space.

A similar suggestion was made a few years later by a French scientist, the Marquis de Laplace, apparently independent of Michell. Interestingly, Laplace included it only in the first and second editions of his book The System of the World, leaving it out of later editions. Perhaps he decided it was a crazy idea—the particle theory of light went out of favor during the nineteenth century because it seemed that everything could be explained using the wave theory. In fact, it is not really consistent to treat light like cannonballs in Newton’s theory of gravity because the speed of light is fixed. A cannonball fired upward from the earth will be slowed down by gravity and will eventually stop and fall back; a photon, however, must continue upward at a constant speed. A consistent theory of how gravity affects light did not come along until Einstein proposed general relativity in 1915, and the problem of understanding what would happen to a massive star, according to general relativity, was first solved by a young American, Robert Oppenheimer, in 1939.

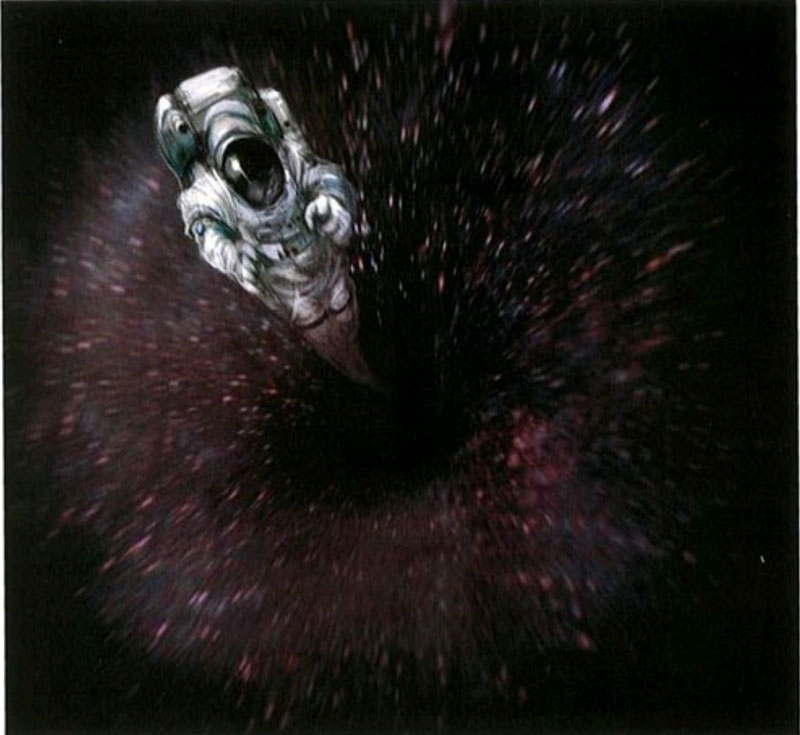

The picture that we now have from Oppenheimer’s work is as follows. The gravitational field of the star changes the paths of passing light rays in space-time from what they would have been had the star not been present. This is the effect that is seen in the bending of light from distant stars observed during an eclipse of the sun. The paths followed in space and time by light are bent slightly inward near the surface of the star. As the star contracts, it becomes denser, so the gravitational field at its surface gets stronger. (You can think of the gravitational field as emanating from a point at the center of the star; as the star shrinks, points on its surface get closer to the center, so they feel a stronger field.) The stronger field makes light paths near the surface bend inward more. Eventually, when the star has shrunk to a certain critical radius, the gravitational field at the surface becomes so strong that the light paths are bent inward to the point that light can no longer escape.

According to the theory of relativity, nothing can travel faster than light. Thus if light cannot escape, neither can anything else; everything is dragged back by the gravitational field. The collapsed star has formed a region of space-time around it from which it is not possible to escape to reach a distant observer. This region is the black hole. The outer boundary of a black hole is called the event horizon. Today, thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope and other telescopes that focus on X-rays and gamma rays rather than visible light, we know that black holes are common phenomena—much more common than people first thought. One satellite discovered fifteen hundred black holes in just one small area of sky. We have also discovered a black hole in the center of our galaxy, with a mass more than one million times that of our sun. That supermassive black hole has a star orbiting it at about 2 percent the speed of light, faster than the average speed of an electron orbiting the nucleus in an atom!

In order to understand what you would see if you were watching a massive star collapse to form a black hole, it is necessary to remember that in the theory of relativity there is no absolute time. In other words, each observer has his own measure of time. The passage of time for someone on a star’s surface will be different from that for someone at a distance, because the gravitational field is stronger on the star’s surface.

Suppose an intrepid astronaut is on the surface of a collapsing star and stays on the surface as it collapses inward. At some time on his watch—say, 11:00—the star would shrink below the critical radius at which the gravitational field becomes so strong that nothing can escape. Now suppose his instructions are to send a signal every second, according to his watch, to a spaceship above, which orbits at some fixed distance from the center of the star. He begins transmitting at 10:59:58, that is, two seconds before 11:00. What will his companions on the spaceship record?

We learned from our earlier thought experiment aboard the rocket ship that gravity slows time, and the stronger the gravity, the greater the effect. The astronaut on the star is in a stronger gravitational field than his companions in orbit, so what to him is one second will be more than one second on their clocks. And as he rides the star’s collapse inward, the field he experiences will grow stronger and stronger, so the interval between his signals will appear successively longer to those on the spaceship. This stretching of time would be very small before 10:59:59, so the orbiting astronauts would have to wait only very slightly more than a second between the astronaut’s 10:59:58 signal and the one that he sent when his watch read 10:59:59. But they would have to wait forever for the 11:00 signal.

Everything that happens on the surface of the star between 10:59:59 and 11:00 (by the astronaut’s watch) would be spread out over an infinite period of time, as seen from the spaceship. As 11:00 approached, the time interval between the arrival of successive crests and troughs of any light from the star would get successively longer, just as the interval between signals from the astronaut does. Since the frequency, of light is a measure of the number of its crests and troughs per second, to those on the spaceship the frequency of the light from the star will get successively lower. Thus its light would appear redder and redder (and fainter and fainter). Eventually, the star would be so dim that it could no longer be seen from the spaceship: all that would be left would be a black hole in space. It would, however, continue to exert the same gravitational force on the spaceship, which would continue to orbit.

This scenario is not entirely realistic, however, because of the following problem. Gravity gets weaker the farther you are from the star, so the gravitational force on our intrepid astronaut’s feet would always be greater than the force on his head. This difference in the forces would stretch him out like spaghetti or tear him apart before the star had contracted to the critical radius at which the event horizon formed! However, we believe that there are much larger objects in the universe, such as the central regions of galaxies, which can also undergo gravitational collapse to produce black holes, like the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. An astronaut on one of these would not be torn apart before the black hole formed. He would not, in fact, feel anything special as he reached the critical radius, and he could pass the point of no return without noticing it— though to those on the outside, his signals would again become further and further apart, and eventually stop. And within just a few hours (as measured by the astronaut), as the region continued to collapse, the difference in the gravitational forces on his head and his feet would become so strong that again it would tear him apart.

Sometimes, when a very massive star collapses, the outer regions of the star may get blown off in a tremendous explosion called a supernova. A supernova explosion is so huge that it can give off more light than all the other stars in its galaxy combined. One example of this is the supernova whose remnants we see as the Crab Nebula. The Chinese recorded it in 1054. Though the star that exploded was five thousand light-years away, it was visible to the naked eye for months and shone so brightly that you could see it even during the day and read by it at night. A supernova five hundred light-years away— one-tenth as far—would be one hundred times brighter and could literally turn night into day. To understand the violence of such an explosion, just consider that its light would rival that of the sun, even though it is tens of millions of times farther away. (Recall that our sun resides at the neighborly distance of eight light-minutes.) If a supernova were to occur close enough, it could leave the earth intact but still emit enough radiation to kill all living things. In fact, it was recently proposed that a die-off of marine creatures that occurred at the interface of the Pleistocene and Pliocene epochs about two million years ago was caused by cosmic ray radiation from a supernova in a nearby cluster of stars called the Scorpius-Centaurus association. Some scientists believe that advanced life is likely to evolve only in regions of galaxies in which there are not too many stars—"zones of life"— because in denser regions phenomena such as supernovas would be common enough to regularly snuff out any evolutionary beginnings. On the average, hundreds of thousands of supernovas explode somewhere in the universe each day. A supernova happens in any particular galaxy about once a century. But that’s just the average. Unfortunately—for astronomers at least—the last supernova recorded in the Milky Way occurred in 1604, before the invention of the telescope.

The leading candidate for the next supernova explosion in our galaxy is a star called Rho Cassiopeiae. Fortunately, it is a safe and comfortable ten thousand light-years from us. It is in a class of stars known as yellow hypergiants, one of only seven known yellow hypergiants in the Milky Way. An international team of astronomers began to study this star in 1993. In the next few years they observed it undergoing periodic temperature fluctuations of a few hundred degrees. Then in the summer of 2000, its temperature suddenly plummeted from around 7,000 degrees to 4,000 degrees Celsius. During that time, they also detected titanium oxide in the star’s atmosphere, which they believe is part of an outer layer thrown off from the star by a massive shock wave.

In a supernova, some of the heavier elements produced near the end of the star’s life are flung back into the galaxy and provide some of the raw material for the next generation of stars. Our own sun contains about 2 percent of these heavier elements. It is a second- or third-generation star, formed some five billion years ago out of a cloud of rotating gas containing the debris of earlier supernovas. Most of the gas in that cloud went to form the sun or got blasted away, but small amounts of the heavier elements collected together to form the bodies that now orbit the sun as planets like the earth. The gold in our jewelry and the uranium in our nuclear reactors are both remnants of the supernovas that occurred before our solar system was born!

When the earth was newly condensed, it was very hot and without an atmosphere. In the course of time, it cooled and acquired an atmosphere from the emission of gases from the rocks. This early atmosphere was not one in which we could have survived. It contained no oxygen, but it did contain a lot of other gases that are poisonous to us, such as hydrogen sulfide (the gas that gives rotten eggs their smell). There are, however, other primitive forms of life that can flourish under such conditions. It is thought that they developed in the oceans, possibly as a result of chance combinations of atoms into large structures, called macromolecules, that were capable of assembling other atoms in the ocean into similar structures. They would thus have reproduced themselves and multiplied. In some cases there would be errors in the reproduction. Mostly these errors would have been such that the new macromolecule could not reproduce itself and eventually would have been destroyed. However, a few of the errors would have produced new macromolecules that were even better at reproducing themselves. They would have therefore had an advantage and would have tended to replace the original macromolecules. In this way a process of evolution was started that led to the development of more and more complicated, self-reproducing organisms. The first primitive forms of life consumed various materials, including hydrogen sulfide, and released oxygen. This gradually changed the atmosphere to the composition that it has today, and allowed the development of higher forms of life such as fish, reptiles, mammals, and ultimately the human race.

The twentieth century saw man’s view of the universe transformed: we realized the insignificance of our own planet in the vastness of the universe, and we discovered that time and space were curved and inseparable, that the universe was expanding, and that it had a beginning in time.

The picture of a universe that started off very hot and cooled as it expanded was based on Einstein’s theory of gravity, general relativity. That it is in agreement with all the observational evidence that we have today is a great triumph for that theory. Yet because mathematics cannot really handle infinite numbers, by predicting that the universe began with the big bang, a time when the density of the universe and the curvature of space-time would have been infinite, the theory of general relativity predicts that there is a point in the universe where the theory itself breaks down, or fails. Such a point is an example of what mathematicians call a singularity. When a theory predicts singularities such as infinite density and curvature, it is a sign that the theory must somehow be modified. General relativity is an incomplete theory because it cannot tell us how the universe started off.

In addition to general relativity, the twentieth century also spawned another great partial theory of nature, quantum mechanics. That theory deals with phenomena that occur on very small scales. Our picture of the big bang tells us that there must have been a time in the very early universe when the universe was so small that, even when studying its large-scale structure, it was no longer possible to ignore the small-scale effects of quantum mechanics. We will see in the next chapter that our greatest hope for obtaining a complete understanding of the universe from beginning to end arises from combining these two partial theories into a single quantum theory of gravity, a theory in which the ordinary laws of science hold everywhere, including at the beginning of time, without the need for there to be any singularities.

Contents

-

Chapter 1

Thinking about the universe

-

Chapter 2

Our evolving picture of the universe

-

Chapter 3

The nature of a scientific theory

-

Chapter 4

Newton's Universe

-

Chapter 5

Relativity

-

Chapter 6

Curved Space

-

Chapter 7

The expanding Universe

-

Chapter 8

The big bang, black holes, and the evolution of the universe

-

Chapter 9

Quantum Gravity

-

Chapter 10

Wormholes and time travel

-

Chapter 11

The forces of nature and the unification of physics

-

Chapter 12

Conclusion