The expanding Universe

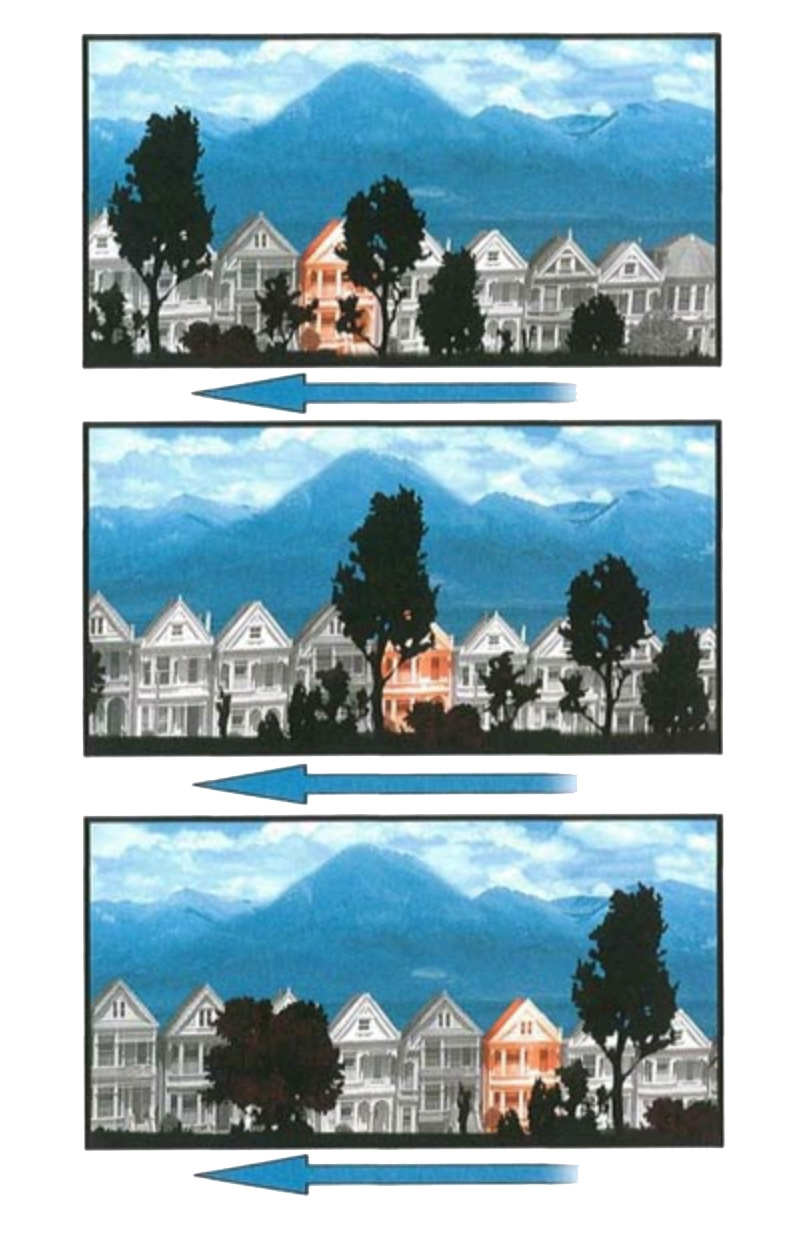

If you look at the sky on a clear, moonless night, the brightest objects you see are likely to be the planets Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. There will also be a very large number of stars, which are just like our own sun but much farther from us. Some of these fixed stars do, in fact, appear to change very slightly their positions relative to each other as the earth orbits around the sun. They are not really fixed at all! This is because they are comparatively near to us. As the earth goes around the sun, we see the nearer stars from different positions against the background of more distant stars. The effect is the same one you see when you are driving down an open road and the relative positions of nearby trees seem to change against the background of whatever is on the horizon. The nearer the trees, the more they seem to move. This change in relative position is called parallax. (See illustration.) In the case of stars, it is fortunate, because it enables us to measure directly the distance of these stars from us.

As we mentioned in Chapter 1, the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is about four light-years, or twenty-three million million miles, away. Most of the other stars that are visible to the naked eye lie within a few hundred light-years of us. Our sun, for comparison, is a mere eight light-minutes away! The visible stars appear spread all over the night sky but are particularly concentrated in one band, which we call the Milky Way. As long ago as 1750, some astronomers were suggesting that the appearance of the Milky Way could be explained if most of the visible stars lie in a single disklike configuration, one example of what we now call a spiral galaxy. Only a few decades later, the astronomer Sir William Herschel confirmed this idea by painstakingly cataloguing the positions and distances of vast numbers of stars. Even so, this idea gained complete acceptance only early in the twentieth century We now know that the Milky Way-our galaxy—is about one hundred thousand lightyears across and is slowly rotating; the stars in its spiral arms orbit around its center about once every several hundred million years. Our sun is just an ordinary, average-sized yellow star near the inner edge of one of the spiral arms. We have certainly come a long way since Aristotle and Ptolemy, when we thought that the earth was the center of the universe!

Our modern picture of the universe dates back only to 1924, when the American astronomer Edwin Hubble demonstrated that the Milky Way was not the only galaxy. He found, in fact, many others, with vast tracts of empty space between them. In order to prove this, Hubble needed to determine the distances from the earth to the other galaxies. But these galaxies were so far away that, unlike nearby stars, their positions really do appear fixed. Since Hubble couldn’t use the parallax on these galaxies, he was forced to use indirect methods to measure their distances. One obvious measure of a star’s distance is its brightness. But the apparent brightness of a star depends not only on its distance but also on how much light it radiates (its luminosity). A dim star, if near enough, will outshine the brightest star in any distant galaxy. So in order to use apparent brightness as a measure of its distance, we must know a star’s luminosity.

The luminosity of nearby stars can be calculated from their apparent brightness because their parallax enables us to know their distance.

Hubble noted that these nearby stars could be classified into certain types by the kind of light they give off. The same type of stars always had the same luminosity. He then argued that if we found these types of stars in a distant galaxy, we could assume that they had the same luminosity as the similar stars nearby. With that information, we could calculate the distance to that galaxy. If we could do this for a number of stars in the same galaxy and our calculations always gave the same distance, we could be fairly confident of our estimate. In this way, Hubble worked out the distances to nine different galaxies.

Today we know that stars visible to the naked eye make up only a minute fraction of all the stars. We can see about five thousand stars, only about .0001 percent of all the stars in just our own galaxy, the Milky Way. The Milky Way itself is but one of more than a hundred billion galaxies that can be seen using modern telescopes—and each galaxy contains on average some one hundred billion stars. If a star were a grain of salt, you could fit all the stars visible to the naked eye on a teaspoon, but all the stars in the universe would fill a ball more than eight miles wide.

Stars are so far away that they appear to us to be just pinpoints of light. We cannot see their size or shape. But, as Hubble noticed, there are many different types of stars, and we can tell them apart by the color of their light. Newton discovered that if light from the sun passes through a triangular piece of glass called a prism, it breaks up into its component colors as in a rainbow. The relative intensities of the various colors emitted by a given source of light are called its spectrum. By focusing a telescope on an individual star or galaxy, one can observe the spectrum of the light from that star or galaxy.

One thing this light tells us is temperature. In 1860, the German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff realized that any material body, such as a star, will give off light or other radiation when heated, just as coals glow when they are heated. The light such glowing objects give off is due to the thermal motion of the atoms within them. It is called blackbody radiation (even though the glowing objects are not black). The spectrum of blackbody radiation is hard to mistake: it has a distinctive form that varies with the temperature of the body. The light emitted by a glowing object is therefore like a thermometer reading. The spectrum we observe from different stars is always in exactly this form: it is a postcard of the thermal state of that star.

Contents

-

Chapter 1

Thinking about the universe

-

Chapter 2

Our evolving picture of the universe

-

Chapter 3

The nature of a scientific theory

-

Chapter 4

Newton's Universe

-

Chapter 5

Relativity

-

Chapter 6

Curved Space

-

Chapter 7

The expanding Universe

-

Chapter 8

The big bang, black holes, and the evolution of the universe

-

Chapter 9

Quantum Gravity

-

Chapter 10

Wormholes and time travel

-

Chapter 11

The forces of nature and the unification of physics

-

Chapter 12

Conclusion